From S² to Sⁿ: Multi‑Axis Polarity and Dimensional Semantics

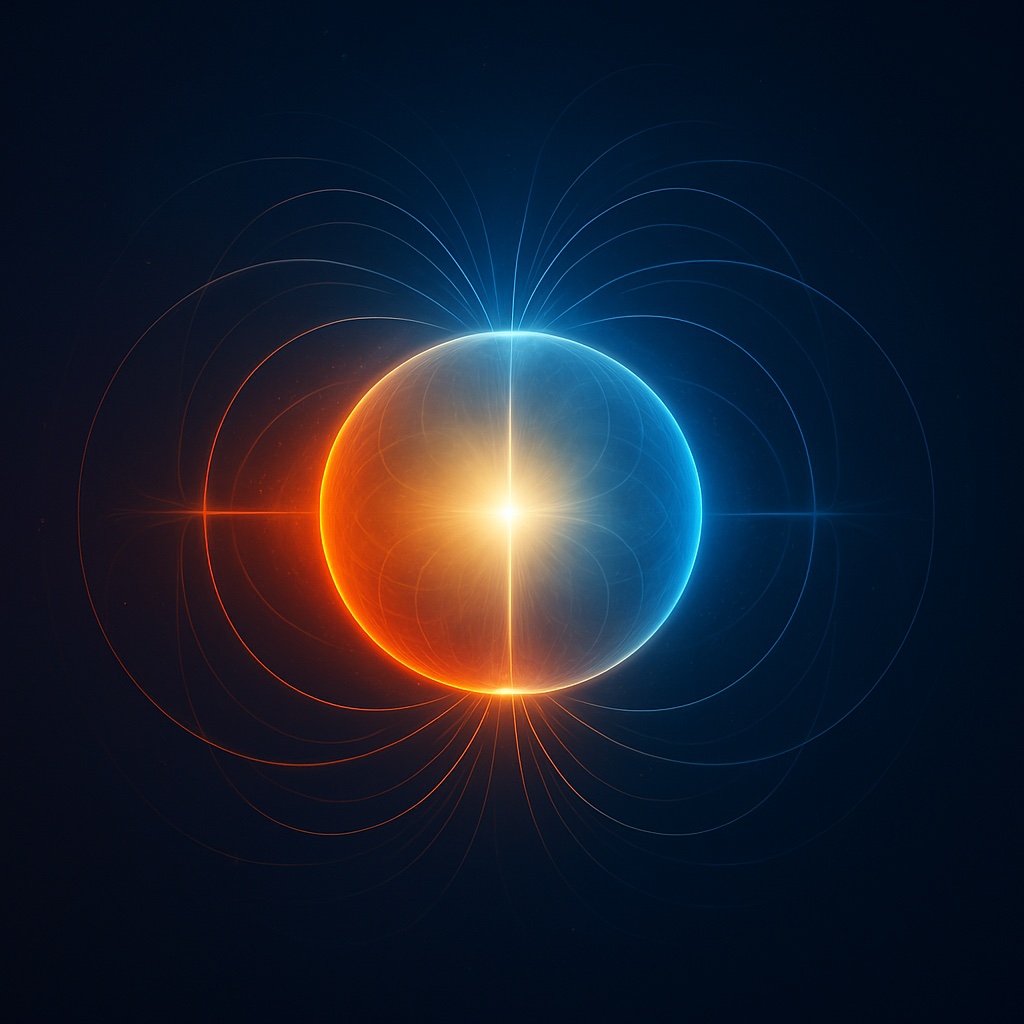

In Part 1, we motivated geometric realization. In Part 2, we developed the geometric atom: a single polarity encoded on the sphere S². In this post, we expand from one polarity to many—moving from S² to the hypersphere Sⁿ. This is where UPA becomes a genuinely multi‑dimensional, multi‑polar, and fully integrative geometric framework.

1. Why We Need More Than One Axis

A single polarity—autonomy ↔ belonging, stability ↔ change—is only one structural dimension. But humans, societies, biological systems, and SGI agents all operate under multiple simultaneous distinctions.

Examples:

- psychology: openness, conscientiousness, self‑regulation, attachment

- neuroscience: inhibition/excitation, exploration/exploitation, local/global control

- social systems: liberty/order, centralization/distribution, inclusion/exclusion

- SGI: safety/performance, explanation/complexity, generality/specificity

A single S² can represent only one such axis.

But UPA asserts (A12):

Systems are always structured by many interacting axes of polarity.

Thus we move to hyperspheres:

- S³ represents two polarities

- S⁴ represents three

- Sⁿ represents n interacting polarities

This expansion preserves all the benefits of polarity on S²—while enabling rich, multi‑aspect structure.

2. Constructing Sⁿ: Each Polarity Becomes a Dimension

On Sⁿ, each semantic polarity axis is represented as a great‑circle direction in a higher‑dimensional space.

For axis i:

- pole pᵢ and its opposite σ(pᵢ) are antipodes along one dimension

- movement toward pᵢ reduces angular distance from that pole

- harmonizing states lie along great‑circle paths in the multi‑dimensional manifold

Formally:

- S² accommodates 1 polarity

- S³ accommodates 2

- S⁴ accommodates 3

- …

- Sⁿ accommodates n

A system’s full semantic state is a single point on Sⁿ that simultaneously encodes:

- orientation relative to each polarity axis

- cross‑axis tradeoffs

- contextual modulations

- harmonic balance

- hierarchical embeddings

This constructs a geometric realization of A12: multi‑axis structure.

3. Orthogonality and Independence of Axes

In the ideal case, each polarity axis is:

- orthogonal to all others,

- encoding a semantically independent dimension,

- preserving clean interpretability.

Examples:

- autonomy ↔ belonging is separate from stability ↔ change

- analytic ↔ intuitive is separate from local ↔ global

But UPA is not rigid—axes can also be:

- oblique (partially correlated)

- curved (structurally dependent)

- hierarchically conditioned by higher levels ℓ (A11)

Dimensional semantics (C.3a) specifies exactly how axes relate:

- how they are named

- how they interact

- how drift and re‑anchoring work

This preserves meaning even as systems learn.

4. Dimensional Semantics: Giving Meaning to Coordinates

Each coordinate dimension on Sⁿ corresponds to a named semantic axis.

Examples:

- Axis 1 → autonomy ↔ belonging

- Axis 2 → stability ↔ change

- Axis 3 → analytic ↔ holistic

- Axis 4 → safety ↔ performance

- Axis 5 → local ↔ global

Dimensional semantics defines:

- the ontology of the axis

- how poles are interpreted

- what transformations are valid

- how cross‑axis mappings maintain coherence

This makes Sⁿ interpretable, not arbitrary.

5. Cross‑Axis Harmony and Multi‑Dimensional Viability

With many polarities active, harmony (A15) generalizes:

Global harmony = alignment across all active polarity axes.

This becomes a function over an entire coordinate vector.

- Balanced configurations lie near the manifold’s “center” (in angular terms).

- Extreme positions cluster near particular poles.

- Context changes axis weights dynamically (A7).

This is the geometric grounding for T4 (multi‑axis tradeoff theorem):

- improving along one axis may worsen another

- viable optima lie on a harmony‑constrained surface

Sⁿ turns qualitative tradeoffs into measurable geometry.

6. Movement and Integration in Sⁿ

Movement on Sⁿ follows geodesics—minimal‑distortion paths.

In multi‑axis space, these paths:

- reflect multi‑aspect updates

- represent integrative transformations

- are context‑shaped by vector fields (C.7)

- preserve polarity and harmony constraints

Examples:

- Growth toward openness + away from rigidity

- SGI reasoning shifting toward safety while moderating performance

- Group identity integrating competing values under a shared context

Sⁿ provides the full geometry of multi‑dimensional integration.

7. Novelty as Dimensional Growth (Sⁿ → Sⁿ⁺Δ)

UPA includes novelty and emergence (A12, A17).

In geometric terms:

Novel distinctions create new dimensions.

This produces temporary or permanent expansion to Sⁿ⁺Δ.

Effects:

- new σ‑pairs appear

- new axes become available

- new regions and trajectories open

After learning stabilizes:

- some axes become permanent

- others collapse back (projection)

Novelty excursions are how SGI—and humans—acquire new representational capacities.

8. Hierarchical Embeddings (Levels ℓ)

Recursive identity (A11) requires representation at multiple resolutions.

Sⁿ supports hierarchical nesting via ℓ:

- Level 0: coarse distinctions

- Level 1: finer distinctions

- Level 2: even more refined semantic structure

Each level is a higher‑dimensional embedding that:

- refines meaning

- preserves polarity structure

- supports identity continuity across scales

This allows SGI to:

- reason coarsely when uncertain

- refine representations when necessary

- remain stable under complexity

9. Why Sⁿ Matters for SGI, Psychology, and Neuroscience

SGI / Siggy

Siggy represents meaning as a point on Sⁿ.

- dimensions encode interpretable semantic distinctions

- learning updates use tangent‑space gradients

- safety uses harmony‑based viability thresholds

- novelty expands dimensionality under pressure

This yields a stable, certifiable SGI architecture.

Psychology

Many psychological models decompose into multi‑axis polarities:

- Big Five

- Jungian functions

- self/other

- stability/neuroticism vs. resilience

Sⁿ offers a unified geometric home for these.

Neuroscience

Opponent processes generalize naturally:

- many circuits operate across multiple functional axes

- neural manifolds often resemble curved spaces

- dimensional growth resembles developmental plasticity

Sⁿ provides a formal model connecting these domains.

10. Summary: What Sⁿ Achieves

Moving from S² to Sⁿ gives UPA:

- a multi‑dimensional, interpretable semantic space

- a geometry for complex tradeoffs

- a foundation for SGI reasoning and certification

- a structure for hierarchy, novelty, and integration

- a unified mathematical model across psychology, neuroscience, and social systems

S² is the geometric atom.

Sⁿ is the semantic molecule.

Next in the Series: Part 4 — Learning on Curved Spaces (Arithmetic & Calculus on Sⁿ)

Part 4 will introduce:

- tangent‑space updates,

- exponential map projection,

- harmony‑guided gradients,

- cross‑axis learning,

- and curvature‑aware optimization.

Ready when you are.

Leave a comment